“Writing well is not just an option for young people – it is a necessity.”

Graham & Perin, 2007

The National Literacy Trust recently warned us that young people’s enjoyment of writing has reduced by a staggering 26% over the last 13 years (Clark et al, 2023).

Its research reveals that only 1 in 3 (34.6%) children and young people aged 8 to 18 say that they enjoy writing in their free time. It also highlights the sharp decline in writing attainment as recorded by statutory assessment data.

To what can we attribute this decline in motivation and enjoyment in writing? The report suggests the pandemic has affected writing enjoyment, regardless of age, gender or levels of disadvantage.

While it does not offer reasons why this may be the case, it will surely be due to several factors, not least the disruption of routines, adapting to new learning environments, increased screen-time, and limited access to resources as well as, in some cases, encouragement.

Yet, vitally, the National Literacy Trust report finds that young people prefer writing at school due to the support and guidance provided by the teacher. This guidance and support may ensure that students have the structures in place to assist them in, for example, activating prior knowledge, applying strategies for writing, and reflecting on strengths and challenges.

In a recent article – Inside the primary writing wars – education writer Helen Amass hypothesises that the “crisis” in writing may be due to the lack of attention it receives as compared to reading in primary schools. The same may be true in secondary.

Almost all Ofsted inspections, post-pandemic, inspect reading in secondary schools, but the same cannot be said for writing.

The Not So Simple View of Writing

Writing is incredibly effortful – it is a complex and demanding task, requiring the integration of various cognitive processes (Breadmore et al, 2019).

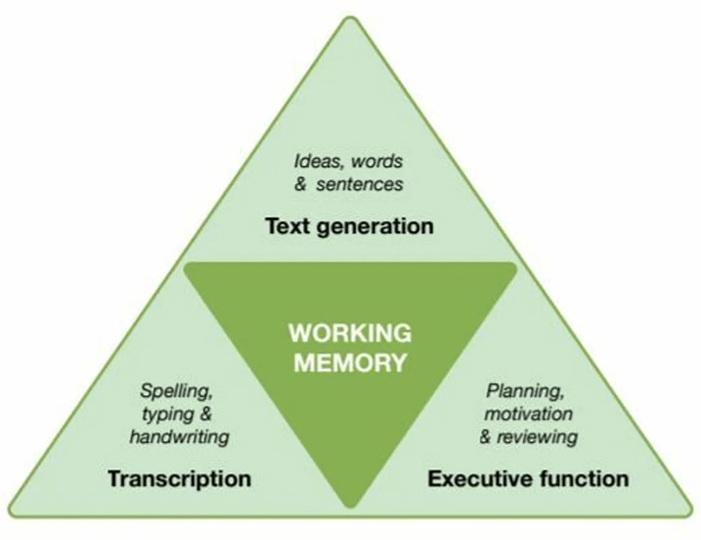

The Simple View of Writing, as proposed by Berninger et al (2002) – and which was expanded into The Not So Simple View of Writing (Berninger & Amtmann, 2003; Berninger & Winn, 2006) – suggests that writing development depends on three types of skills, all limited by working memory capacities.

- Text generation.

- Self-regulation.

Getting writing right: Based on the Not So Simple View of Writing (see Berninger & Amtmann, 2003; Berninger & Winn, 2006)

Further, according to Debra Myhill, professor emerita of language and literacy education at the University of Exeter, the cognitive demands of writing do not decrease with experience (cited by Amass, 2023).

The Education Endowment Foundation’s literacy development evidence review (Breadmore et al, 2019) explores research (McCutchen, 2011) examining the self-talk or thought processes of writers at different skill levels – experts, beginners, and intermediate writers.

Experts, in contrast to the other groups, engage in extensive self-talk while writing, considering factors like the reader's perspective, long-term knowledge, and sentence structure.

Novice writers tend to produce self-talk that closely resembles spoken language, reflecting a more literal translation of their thoughts into writing.

As such, this type of metacognitive self-talk is worth modelling to students to develop their skills and therefore their enjoyment of writing.

Metacognitive approaches to support the complexity of writing

Metacognitive instruction is recognised as effective for teaching writing and improving overall academic achievement. The teacher’s role in implementing metacognitive processes is crucial in developing this skill.

Braund and Soleas (2019) assert that: “Research has consistently shown that explicit instruction about metacognitive processes is necessary for developing metacognitive thinking.”

They add that metacognition can be conceptualised as having “three dynamic and interrelated components”. These are: metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive regulation, and metacognitive experiences. All three components need to be learnt and practised.

Metacognitive knowledge

- Thoughts and beliefs that an individual has about their cognitive capabilities. These thoughts can be in relation to one’s self, the task, or strategies.

- The knowledge can be declarative (“knowing that”), procedural (“knowing how”), or conditional (“knowing when”) – (see Flavell, 1979).

Metacognitive regulation

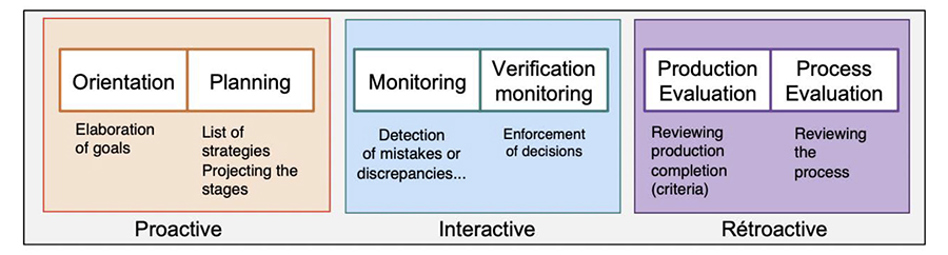

- An individual’s capacity to monitor and control their learning.

- This component can be broken down further into three stages: Planning, monitoring, and evaluating (Flavell, 1979).

Metacognitive experiences

- Judgements and feelings that an individual has about their learning and thinking, such as: feelings of confidence, or difficulty (Ben-David & Orion, 2013; Efklides, 2006).

Through incorporating metacognitive practices, students become more aware of their writing processes and develop effective writing skills.

The research paper Teaching children to write – a meta-analysis of writing intervention (Koster et al, 2015), cites one study from which found goal-setting, strategy instruction, feedback, text structure instruction, and peer assistance as having significant positive effects on improving writing.

It is confirmation of the complexity of writing instruction and that without metacognitive support at an instructional level we will often find students bemoaning: “I don’t know how to start.”

The research paper – Teaching writing: With or without metacognition? – details an exploratory study of 11 and 12-year-olds students writing a book review (Colognesi et al, 2020) and outlines the results of an experiment whereby the authors attempted the answer the question: “What effects do metacognitive questions have on students' writing skills?”

They conclude that students being asked metacognitive questions during planned activities led to significant progress in their writing skills. They assert that there are three ways in which information about learners’ metacognitive activities can be solicited through questioning (metacognitive mediations) which can be asked before, during or after the tasks. The paper includes the following examples:

Significant progress: Six types of metacognitive mediation (source: Colognesi & Van Nieuwenhoven, 2016, cited in Colognesi et al, 2020).

Furthermore, in the paper, Colognesi et al (2020) use three ways to encourage metacognitive thinking, which can occur before, during and/or after a task:

- Think-aloud protocols: Students can be asked to verbalise aloud about their thought processes.

- Judgements of learning: Asking students to make judgements about their ability to redo a task as a self-assessment measure.

- Confidence ratings: Asking students to position themselves in relation to the task by giving a confidence rating.

Meanwhile, Ramazan Goctu’s paper Metacognitive strategies in academic writing (2017) suggests that to successfully develop academic writing through metacognition explicit instruction is vital – that is, clearly explain what metacognition is and label specific processes. He suggests:

- Planning: Teach students to plan their writing by setting clear goals, identifying the purpose of their writing, considering the target audience, brainstorming ideas, and selecting appropriate strategies. Encourage them to create outlines or mind-maps to organise their thoughts.

- Monitoring: Show students how to monitor their writing as they work on it. They should focus on global features such as content and organisation, as well as local aspects like grammar and mechanics. Encourage them to check their progress regularly to ensure they are on track.

- Evaluating: Teach students how to evaluate their writing after they have completed a draft. Emphasise the importance of revising and editing to improve both global and local writing features.

Of course, each of these stages needs to be modelled and scaffolded with deliberate repetition of processes to reinforce the idea that improvement comes with practice.

This metacognitive approach supports the recommendation given in the EEF’s Improving secondary literacy guidance report (Quigley & Coleman, 2021) to “break down complex writing tasks”.

Specifically, the guidance suggests the explicit teaching of planning strategies, including the use of graphic organisers and that “students should develop proficiency in various strategies and learn to choose based on the task and audience”. The guidance report also supports the findings that developing self-talk in writing tasks aids self-regulation.

Final thoughts

In the face of a concerning decline in students' enjoyment of writing and a notable drop in writing attainment, incorporating metacognitive strategies emerges as a crucial tool for teachers, including:

- Incorporating metacognitive strategies – to enhance students' awareness of their writing processes.

- Facilitating goal-setting, strategy instruction, feedback, text structure instruction, and peer assistance.

- Explicit instruction in metacognition, including planning, monitoring, and evaluating writing.

- Utilising metacognitive questions during planned activities, such as think-aloud protocols, judgements of learning, and confidence ratings.

- Debbie Tremble is assistant headteacher for teaching and learning at John Taylor High School in Staffordshire. She has 20 years’ experience in education, undertaking a variety of roles including head of English and trust lead for English and literacy. Debbie is an SLE for English, ELE for Staffordshire Research School, and is currently partaking in an NPQLTD. Follow her on X (Twitter) @mrs_tremble. Find her previous articles and webinar appearances for SecEd via www.sec-ed.co.uk/authors/debbie-tremble

The SecEd Podcast

A recent episode of the SecEd Podcast interviews Alex Quigley, the author of Closing the Writing Gap, and discusses strategies to support the teaching of writing in the secondary school. Find this episode via www.sec-ed.co.uk/content/podcasts/the-seced-podcast-closing-the-writing-gap

Further information & resources

- Amass: Inside the primary writing wars, Tes, 2023: http://tinyurl.com/yfbh6c5y

- Ben-David & Orion: Teachers’ voices on integrating metacognition into science education, International Journal of Science Education (35:18), 2013.

- Berninger & Amtmann: Preventing written expression disabilities through early and continuing assessment and intervention for handwriting and/or spelling problems: Research into practice. In Handbook of Learning Disabilities, Swanson, Harris & Graham (eds), Guilford Press, 2003.

- Berninger & Winn: Implications of advancements in brain research and technology for writing development, writing instruction, and educational evolution. In Handbook of Writing Research, MacArthur & Fitzgerald (eds), Guilford Press, 2006.

- Berninger et al: Writing and reading: Connections between language by hand and language by eye, Journal of Learning Disabilities, (35,1), 2002: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15490899/

- Braund & Soleas: The struggle is real: Metacognitive conceptualizations, actions, and beliefs of pre-service and in-service teachers, Teachers’ Professional Development in Global Contexts, 2019.

- Breadmore et al: Literacy development: Evidence review, Education Endowment Foundation, 2019: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/evidence-reviews/literacy-development

- Clark et al: Children and young people’s writing in 2023, National Literacy Trust, 2023: http://tinyurl.com/5hba7d42

- Colognesi et al: Teaching writing – with or without metacognition? An exploratory study of 11 to 12-year-old students writing a book review, International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 2020: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1262736.pdf

- Efklides: Metacognition and affect: What can metacognitive experiences tell us about the learning process? Educational Research Review (1), 2006.

- Flavell: Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry, American Psychologist (34,10), 1979: https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

- Goctu: Metacognitive strategies in academic writing, Journal of Education in Black Sea Region (2, 2), 2017.

- Graham & Perin: Writing Next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools, Alliance for Excellent Education, 2007.

- Koster et al: Teaching children to write: A meta-analysis of writing intervention research, Journal of Writing Research (7), 2015: https://jowr.org/index.php/jowr/article/view/661/627

- McCutchen: From novice to expert: Implications of language skills and writing-relevant knowledge for memory during the development of writing skill, Journal of Writing Research (3,1), 2011.

- Quigley & Coleman: Improving literacy in secondary schools: Guidance report, EEF, 2021: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/guidance-reports/literacy-ks3-ks4